In this chapter, you will learn how to read from and write to files. In most real-world applications, you'll be working with datasets that are too large to include in a program in a predefined string or collection.

But you'll find that a lot of the operations on files are similar to what we've been using when downloading files from the web.

Creating a file and writing to it

The File class supplies the basic methods to manipulate files. The following script opens a new textfile in "write" mode and then writes "Hello file!" to it:

fname = "sample.txt"

somefile = File.open(fname, "w")

somefile.puts "Hello file!"

somefile.close

In the file directory from which you run this code, a sample.txt file should now appear, with the words "Hello file!" in it. Some notes:

- I deliberately made this example more wordy than it needs to be to emphasize this: the first line sets fname to just a string that represents the filename. Again, fname is just the filename, not the actual file itself. This also works:

somefile = File.open("sample.txt", "w") somefile.puts "Hello file!" somefile.close - The next line invokes the File class method open, which requires us to pass it two arguments: 1) the filename, represented by a String, and 2) the read/write mode. As you might guess, "w" stands for write.

Warning: Using "w" mode on an existing file will erase the contents of that file. If you want to append to an existing file, use "a" as the second argument.

- The File class has its own puts method. But this one prints to the file instead of to the screen. You can also use write, which does not include a newline character at the end of the string.

- The close method finishes the writing process and prevents any further data operations on the file (though you can reopen it again).

File.open vs open

If you remember back to the tweet-fetching introduction, we executed programs that wrote the contents of Wikipedia to a file on our hard disk:

require "open-uri"

remote_base_url = "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki"

remote_page_name = "Ada_Lovelace"

remote_full_url = remote_base_url + "/" + remote_page_name

remote_data = open(remote_full_url).read

my_local_file = open("my-downloaded-page.html", "w")

my_local_file.write(remote_data)

my_local_file.close

Notice how we didn't have to invoke the use of the File class. I purposefully omitted it then because I wanted to reduce the number of unfamiliar words and conventions in the introduction. Like puts, open is handled by the Kernel class. In this lesson, I've explicitly invoked it as a method of the File class just to make it more obvious that we're dealing with a local file rather than an input stream from a webpage.

So the code snippet above could be written thus:

remote_data = open(remote_full_url).read

my_local_file = File.open("my-downloaded-page.html", "w") Block notation

Instead of assigning a file handle to a variable, like so:

somefile = File.open("sample.txt", "w")

somefile.puts "Hello file!"

somefile.closeYou can use the block convention with File.open:

File.open("sample.txt", "w"){ |somefile| somefile.puts "Hello file!"}The file handle is automatically closed at the end of the block, so no need to call the close method. This is handy in cases when you only need to do all read or write to a file all in one go.

Exercise: Copy Wikipedia's front page to a file using block notation

Using the RestClient gem we learned about in the Methods URL-fetching chapter, write a script that accesses http://en.wikipedia.org/ and copies it to wiki-page.html on your hard drive. http://ruby.bastardsbook.com/files/fundamentals/hamlet.txt.

Solution

require 'rubygems'

require 'rest-client'

wiki_url = "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

wiki_local_filename = "wiki-page.html"

File.open(wiki_local_filename, "w") do |file|

file.write(RestClient.get(wiki_url))

end

Reading from a file

Reading a file uses the same File.open method as before. However, the second argument is an "r" instead of "w".

After the file is opened, you can use a variety of methods to read its content. The most obviously-named method is read, which grabs all the file's contents:

file = File.open("sample.txt", "r")

contents = file.read

puts contents #=> Lorem ipsum etc.

contents = file.read

puts contents #=> ""

Every read operation begins where the last read operation ended. In the case where we've read the entire file (by not passing in a number), the second read call has nothing left to read.

Here's an example of read using the block format

contents = File.open("sample.txt", "r"){ |file| file.read }

puts contents

#=> Lorem ipsum etc. Using readline and readlines

When dealing with delimited files, such as comma-delimited text files, it's more convenient to read the file line by line. The readlines method can draw in all the content and automatically parse it as an array, splitting the file contents by the line breaks.

File.open("sample.txt").readlines.each do |line|

puts line

end

The method readline on the other hand, reads a singular line. Again, each read operation moves the file handle forward in the file. If you keep calling readline until you hit the end of the file and then call it again, you'll get an "end of file" error.

The File class (more specifically, the IO class that File inherits from) contains the eof? method, which returns true if there is no more data in the file to read.

The readline method is often used in conjunction with while or unless:

file = File.open("sample.txt", 'r')

while !file.eof?

line = file.readline

puts line

end

The readline method seems to require more upkeep than readlines. So why use it when you plan on reading an entire file?

Because the latter loads the entire file at once into memory. For most files under a few dozen megabytes, that's probably manageable on your home computer. But this is not good practice if the program is running on a computer that is serving multiple users, especially if the file is massive.

The readline method may require a couple more lines of code, but it's more efficient in most scenarios when extracting something from each line; you aren't operating on the entire file contents at once, and you don't need to store the entirety of each line either.

Exercise: Using readlines

For this exercise, we will use OpenURI's version of open, which gives us a read-only interface for accessing files online:

require 'open-uri'

url = "http://ruby.bastardsbook.com/files/fundamentals/hamlet.txt"

puts open(url).readline

#=> THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK

Write a program that:

- Reads hamlet.txt from the given URL

- Saves it to a local file on your hard drive named "hamlet.txt"

- Re-opens that local version of hamlet.txt and prints out every 42nd line to the screen

Solution

Use readlines and the each_with_index method that we used in the enumerables chapter:

require 'open-uri'

url = "http://ruby.bastardsbook.com/files/fundamentals/hamlet.txt"

local_fname = "hamlet.txt"

File.open(local_fname, "w"){|file| file.write(open(url).read)}

File.open(local_fname, "r") do |file|

file.readlines.each_with_index do |line, idx|

puts line if idx % 42 == 41

end

end

Bonus Exercise: Print only Hamlet's lines

Now that hamlet.txt is on your hard drive, open it again but this time, print only the lines by Hamlet.

If you open up the file, this is what it looks like (Hamlet's speech is highlighted in blue):

Ham. Do not believe it. Ros. Believe what? Ham. That I can keep your counsel, and not mine own. Besides, to be demanded of a sponge, what replication should be made by the son of a king? Ros. Take you me for a sponge, my lord? Ham. Ay, sir; that soaks up the King's countenance, his rewards, his authorities. But such officers do the King best service in the end. He keeps them, like an ape, in the corner of his jaw; first mouth'd, to be last Swallowed. When he needs what you have glean'd, it is but squeezing you and, sponge, you shall be dry again. Ros. I understand you not, my lord. Ham. I am glad of it. A knavish speech sleeps in a foolish ear.

Note that each speaker's name is abbreviated to a few letters and a period. If the speaker's dialogue is longer than a single line, each successive line is indented four spaces.

When someone new speaks, his/her name is indented two spaces in. Also, dialogue ends if there is a blank line.

Hint: I don't think it's possible to do this without a regular expression. If you've been following this book linearly, then you may not know about regexes. They're a way to match patterns of text – such as, any string that has more than five consecutive vowels – rather than just literal characters. They're so useful that it's worth skipping ahead to them; you don't even need to program to use them.

There are several regexes that would work, but this one will suffice:

/^ [A-Z]/Note that there are two spaces after the caret symbol ^. The caret symbol specifies that we want a pattern that starts with the beginning of the line. So when this regex is passed into the match method, it will match any line that begins with two spaces and a capitalized letter. Sample usage:

lines = ["Hello world", " How are you?", "*Fine*, thank you!.", " OK then."]

lines.each do |line|

puts line if line.match(/^ [A-Z]/)

end

The output:

How are you? OK then.

One more hint: match also has an annoying "feature" in which any string passed into it is converted into a regex pattern. So if you wanted to match, say, "Ham.", you would need to escape the period: "Ham\.". The period, in regex syntax, stands for any character (including an empty space). Thus:

if "Honey Ham is my favorite".match("Ham.")

puts "Hey, I just wanted to match 'Ham.' Ham with a dot!"

end

#=> Hey, I just wanted to match 'Ham.' Ham with a dot!

OK, last hint: you might find the string's strip method to be useful.

Solution

This solution uses match two times:

- To match "Ham\." – again, we need to escape the dot with a backslash since the string is converted to a regex by match

- To match the regex /^ [A-Z]/

We're also interested in blank lines, which are any lines in which this is the case:

line.strip.empty? == trueRemember that strip removes all consecutive whitespace from the beginning and end of a line.

When a given line matches "Ham\.", we know that it must be the beginning of some Hamlet dialogue (to my knowledge, Hamlet does not contain any dialogue in which there is the one-word sentence, "Ham.")

Once that criteria has been met, than any line that matches the given regex /^ [A-Z]/ must be a line in which someone new speaks. Or, if a line is blank, then also marks the end of Hamlet's speech. Therefore, we print every line from "Ham." on until the regex is matched or there is a blank line.

is_hamlet_speaking = false

File.open("hamlet.txt", "r") do |file|

file.readlines.each do |line|

if is_hamlet_speaking == true && ( line.match(/^ [A-Z]/) || line.strip.empty? )

is_hamlet_speaking = false

end

is_hamlet_speaking = true if line.match("Ham\.")

puts line if is_hamlet_speaking == true

end

end

This script almost gets it:

Ham. Methinks it is like a weasel.

Ham. Or like a whale.

Ham. Then will I come to my mother by-and-by.- They fool me to the

top of my bent.- I will come by-and-by.

Ham. 'By-and-by' is easily said.- Leave me, friends.

[Exeunt all but Hamlet.]

'Tis now the very witching time of night,

When churchyards yawn, and hell itself breathes out

Contagion to this world. Now could I drink hot blood

It also catches stage directions. We could eliminate that problem with a more specific regular expression, but this isn't bad for now. Hopefully, you're interested enough in regular expressions to check out their chapter.

Closing files

Just as you can open a file for reading or writing, you can close them too. What happens if you don't close a file? Nothing too bad, usually. But try writing a large amount of data to a file and have the program finish immediately after the write operation. When viewing the file immediately after with an external text editor, you might notice that it appears to be incomplete. Re-open it a few seconds later and it should contain what you expect.

File write operations don't happen instantaneously, as disk access is bound by at least the laws of physics. As data queues up to be written, it sits in a memory buffer before actually being written to the hard disk.

A file's close method forces a flush of the pending data. And while "flush" has the real-world meaning of getting rid of waste, in programming, a "flush" merely pushes the data-to-be-written to where you want it to be: a file on the hard drive.

Similar to flushing in the real-world, doing a "flush" is good practice in programming because it frees up memory for the rest of your program and (ideally) ensures that that file is available for other processes to access.

You can close a File by calling its close method:

datafile = File.open("sample.txt", "r")

lines = datafile.readlines

datafile.close

lines.each{ |line| puts line }

Or, you can pass a block into File.open. At the end of the block, the file is automatically closed:

lines = File.open("sample.txt", "r"){ |datafile|

datafile.readlines

}

lines.each{|line| puts line}

File existence and properties

Besides reading and writing, the File and Dir classes have methods that can determine various properties of files, including size, its directory, and whether or not a file with a given name exists.

File.exists?

This is a useful class method that checks whether a file or directory exists and returns true/false:

if File.exists?(filename)

puts "#{filename} exists"

end

I use it often to check whether a directory exists. If false, then I use the Dir.mkdir class method to create it:

dirname = "data-files"

Dir.mkdir(dirname) unless File.exists?dirname

File.open("#{dirname}/new-file.txt", 'w'){|f| f.write('Hello world!')}

The Dir class

The methods of the Dir class are useful in conjunction with file operations.

One of the most useful is Dir.glob, which takes in a directory name and/or a pattern with wildcards and returns an array of filenames:

# count the files in my Downloads directory:

puts Dir.glob('Downloads/*').length #=> 382

# count all files in my Downloads directory and in sub-directories

puts Dir.glob('Downloads/**/*').length #=> 308858

# list just PDF files, either with .pdf or .PDF extensions:

puts Dir.glob('Downloads/*.{pdf,PDF}').join(",\n")

#=> Downloads/About Downloads.pdf,

#=> Downloads/blueprintcss-1-0-cheatsheet-4-2-gjms.pdf,

#=> Downloads/crafting-rails-applications_b3_0.pdf,

#=> Downloads/DOM166.pdf,

#=> Downloads/html5-cheat-sheet.pdf,

#=> Downloads/la_museum_free_days.pdf,

#=> Downloads/mbapm_rec-a.pdf,

#=> Downloads/mbapm_rec.pdf,

#=> Downloads/metaprogramming-ruby_p2_0.pdf,

#=> Downloads/mining-of-massive-datasets-book.pdf,

#=> Downloads/poignant-guide.pdf,

#=> Downloads/PrinterSchedule.pdf

A word of caution: The next few exercises involve using a loop and File operations. Remember how passing in the 'w' parameter to File.open will empty an existing file?

Be careful not to mistakenly pass in a 'w' when you mean to read a group of files.

Exercise: Find the top 10 largest files

Using the Dir.glob and File.size methods, write a script that targets a directory – and all of its subdirectories – and prints out the names of the 10 files that take up the most disk space.

Point your script to any subdirectory. You will obviously get different results than I do.

Hint: This exercise does not require a call to File.open

Solution

DIRNAME = "data-hold"

Dir.glob("#{DIRNAME}/**/*.*").sort_by{|fname| File.size(fname)}.reverse[0..9].each do |fname|

puts "#{fname}\t#{File.size(fname)}"

endThe output:

data-hold/f-fi/explore.data.gov.html 749435 data-hold/f-fi/apps.html 257722 data-hold/f-fi/Los_Angeles_Galaxy.html 256100 data-hold/f-fi/2009_Major_League_Soccer_season.html 249822 data-hold/f-fi/2010_Colorado_Rapids_season.html 236699 data-hold/f-fi/2010_Carolina_RailHawks_FC_season.html 225925 data-hold/f-fi/2010_FIFA_U-20_Women's_World_Cup.html 222390 data-hold/f-fi/2010_Vancouver_Whitecaps_FC_season.html 215580 data-hold/f-fi/2004_Lamar_Hunt_U.S._Open_Cup.html 213927 data-hold/Copyright and Other Rights Pertaining to U.S. Government Works USA.gov_files/jquery-ui-1.8.12.custom.min.js 208528

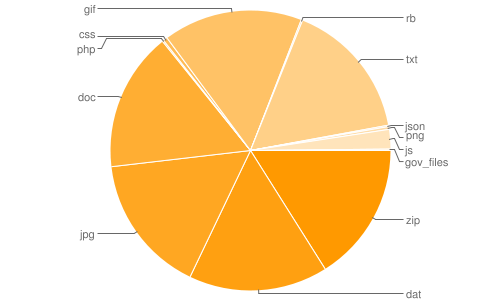

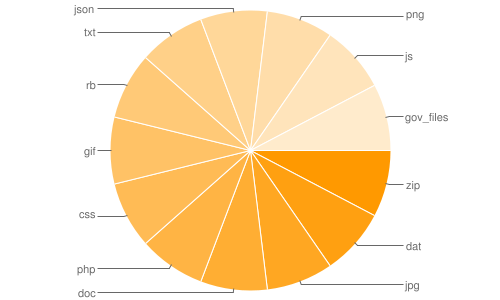

Exercise: Determine file makeup of directories, print to spreadsheet

Read the same directory and subdirectories as in the last exercise and determine:

- A breakdown of file types (normalize the file extensions) by number of files

- A breakdown of file types by bytes of disk space used.

Print the results of this analysis in a single text file, in the following spreadsheet-friendly tab-delimited format:

Filetype Count Bytes

TXT 34 102300

JPG 8 20050010

GIF 5 428400

Solution

DIRNAME = "data-hold"

hash = Dir.glob("#{DIRNAME}/**/*.*").inject({}) do |hsh, fname|

ext = File.basename(fname).split('.')[-1].to_s.downcase

hsh[ext] ||= [0,0]

hsh[ext][0] += 1

hsh[ext][1] += File.size(fname)

hsh

end

File.open("file-analysis.txt", "w") do |f|

hash.each do |arr|

txt = arr.flatten.join("\t")

f.puts txt

puts txt

end

endhtml 346 24336017 zip 176 1499377 dat 149 1309082 jpg 167 1554263 doc 175 1368080 php 1 58452 css 3 38354 gif 176 1555577 rb 1 615 txt 172 1374899 json 1 7391 png 2 8626 js 14 490382 gov_files 1 816

Exercise: Read a text file and create a Google Chart

Reading from the text files generated in the last exercise, use the Google Image Chart API (note that this is different from their Javascript-based Chart API) to draw piecharts based on the data and save those images somewhere on your hard drive.

Read up on the pie chart API here. You can use open-uri to retrieve the file.

Here's a sample image:

https://chart.googleapis.com/chart?cht=p&chd=t:10,20,30,40&chs=500x300&chl=Jan|Feb|Mar|Apr

Solution

require 'open-uri'

BASE_URL = "https://chart.googleapis.com/chart?cht=p&chs=500x300"

rows = File.open("file-analysis.txt"){|f| f.readlines.map{|p| p.strip.split("\t")} }

headers = rows[0]

[1,2].each do |idx|

labels = []

values = []

rows[1..-1].each do |row|

labels << row[0]

values << row[idx]

end

remote_google_img = URI.encode"#{BASE_URL}&chl=#{labels.join('|')}&chd=t:#{values.join(',')}"

puts remote_google_img

File.open('file-pie-chart.png', 'w'){|f|

f.write(open(remote_google_img))

}

end

The two URLs that are output are the Google charts for number of files by filetype and total size of files by filetype, respectively:

http://chart.googleapis.com/chart?cht=p&chs=500x300&chl=zip%7Cdat%7Cjpg%7Cdoc%7Cphp%7Ccss%7Cgif%7Crb%7Ctxt%7Cjson%7Cpng%7Cjs%7Cgov_files&chd=t:176,149,167,175,1,3,176,1,172,1,2,14,1 http://chart.googleapis.com/chart?cht=p&chs=500x300&chl=zip%7Cdat%7Cjpg%7Cdoc%7Cphp%7Ccss%7Cgif%7Crb%7Ctxt%7Cjson%7Cpng%7Cjs%7Cgov_files&chd=t:1499377,1309082,1554263,1368080,58452,38354,1555577,615,1374899,7391,8626,490382,816

Congrats, you're now done with what consists of the "fundamentals" for this book. This doesn't mean you're a full-fledged programmer by any means. But you're at a point to start doing something useful beyond what you've done in push-a-button programs.